- This Is Bizness

- Posts

- The Rise of Search Funds

The Rise of Search Funds

How a Niche Investment Model Is Redefining Entrepreneurship Across the Globally

From the PF team: Hey guys, this is our first attempt at curating various studies and other literature on search funds. Hope this provides some value to the community. We'd love to receive any feedback from you and answer any questions you may have! Just hit reply on this email.

Introduction

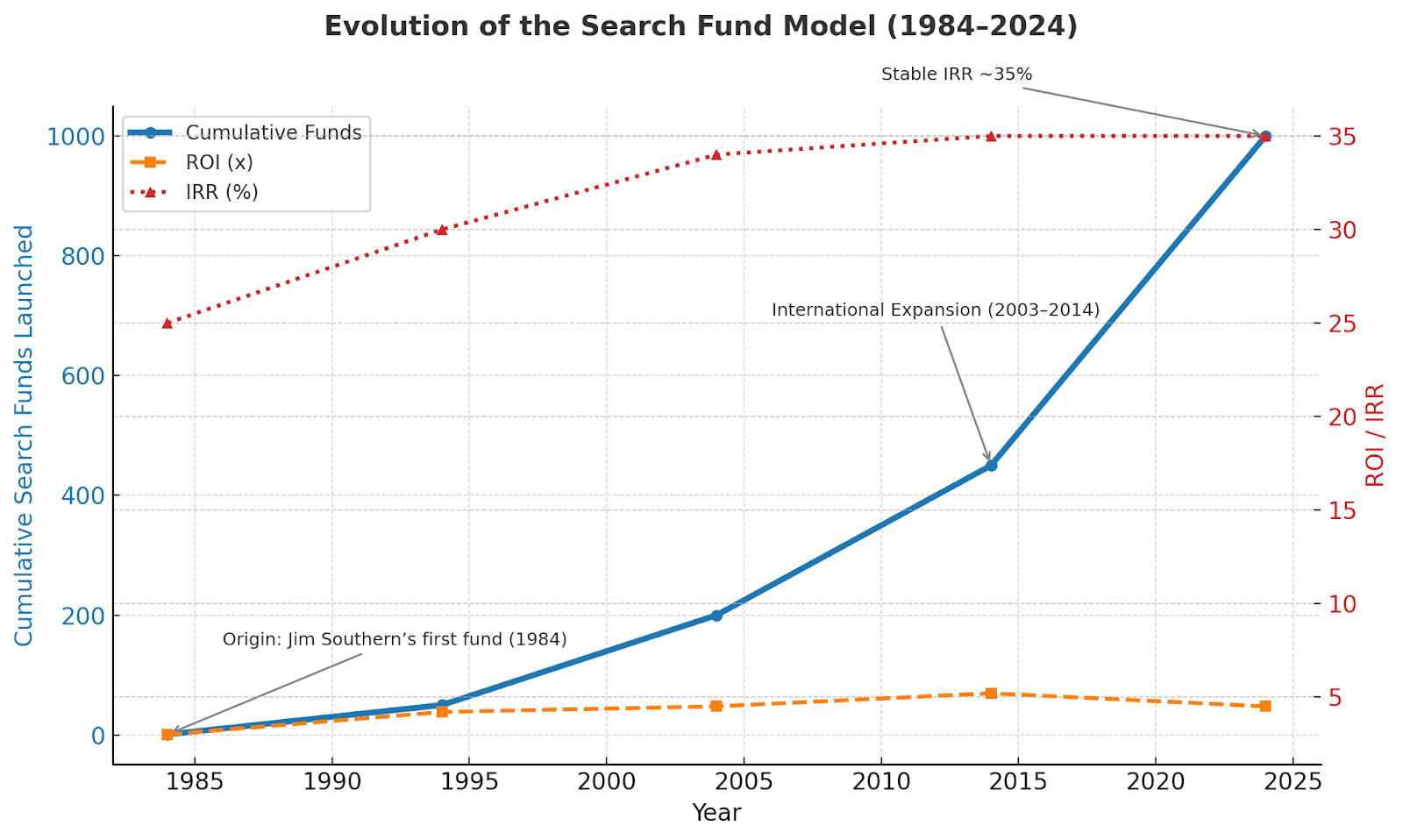

The search fund model as we know it today was born in the early 1980s at Stanford GSB, designed as a vehicle for capable but inexperienced MBA graduates to become CEOs. One of the first deals under this model was when Jim Southern raised a fund in 1984 and acquired Uniform Printing, validating the model’s potential and launching what is now recognized as the first search fund, Nova Capital.

What began as a niche experiment in the 1980s has evolved into a distinct asset class, and career path.

Naturally, evolution has brought variations to the model: institutional “core” searches, self-funded searches, and some hybrid approaches emerging across continents. Each version represents a different balance of risk, ownership, and support. Together, they signal how far the search fund model has evolved beyond its original blueprint.

Here, we trace that evolution. From the early days of search capital to the current wave of independent operators reshaping the lower middle market. For searchers, understanding this evolution isn’t historical trivia, it’s strategic context. The rules of the game are changing, and knowing how they changed is the first step in playing it well.

For the purposes of this article, we’ve used How Search Funds are Redefining Entrepreneurship by HBR, alongside the Stanford Search Fund Study (2024), the IESE Search Fund Studies (2022 & 2024), and foundational materials such as the Search Fund Primer (2021), the Foundational Guide to Self-Funded Search Funds, and IESE’s Search Funds – What Has Made Them Work?

The Searcher: Profile, Pressure, and Performance

Who are the Searchers?

The data on searcher demographics (median age 31–32, typically with an MBA and a background in finance or consulting) paints a clear picture of the resume. However, the intangible qualities that correlate with success are often more telling.

Beyond the resume, studies and investor feedback consistently point to a few key personality traits.

The first is perseverance. The search process is a long, tiring, and emotionally stressful numbers game filled with rejection. The ability to persist through those hardships is paramount. The second is a specific kind of humility; successful searchers are those who demonstrate a willingness to seek, and heed, criticism. Given that most are first-time CEOs, this ability to listen is critical. Finally, searchers need a high degree of flexibility and an aptitude for decision making to navigate the constant trade-offs and uncertainty of the process.

With a 37% failure rate to find any deal in the US/Canada and 63% of LOIs failing after signature, the process is fraught with minefields.

The single biggest, non-obvious mistake is often psychological. The search has a binary, highly emotional outcome, and the clock is always ticking. The median search takes 20 months. The biggest risk identified by veterans is that as a searcher runs out of time, he or she may feel pressured and make bad decisions, leading to a questionable deal getting done, simply out of time pressure.

Solo v.s. Partnered?

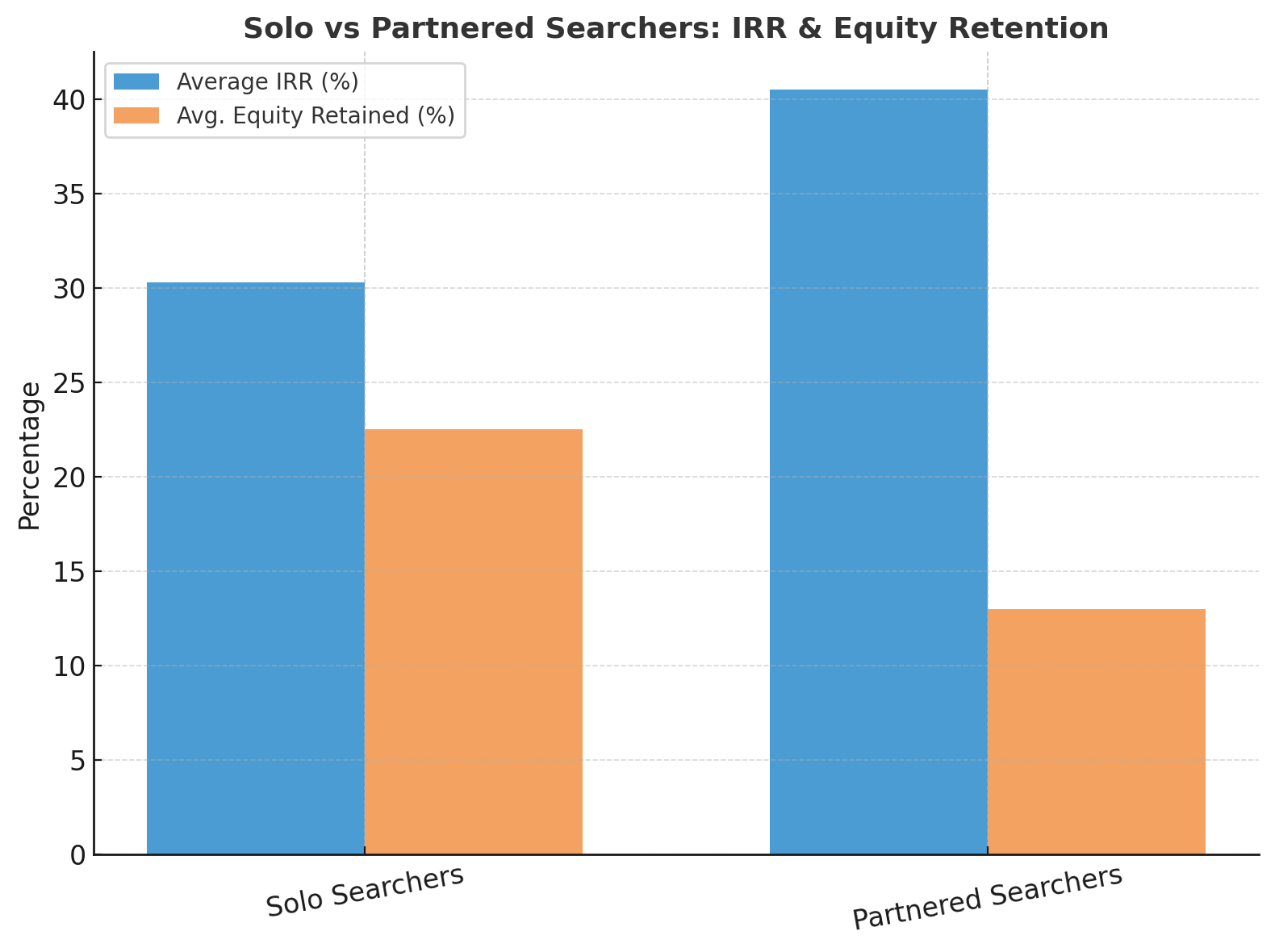

The data presents a paradox: partnered searches historically show a higher aggregate IRR (40.5%) than solo searches (30.3%), likely because having a second view leads to better decisions. Yet, 81% of new funds in 2022–2023 were solo.

The decision is likely a very personal choice. A solo searcher typically retains a 20%–25% equity stake, whereas partners must share a combined 25%–30%. The solo trend is further supported by the fact that five of the six searchers who achieved a 10x+ ROI in the last two years were solo searchers.

If we go back a few years, in 1995, two Stanford MBA graduates, Kevin Taweel and Jim Ellis, launched a partnered search and acquired Road Rescue, a Houston-based dispatch service, for approximately $8 million. Following that, they pivoted the company into the then nascent market for cell phone insurance, renaming it Asurion. The result was the most successful search acquisition to date, with the company being valued at over a billion dollars.

These results are far from anecdotal. Other partnered funds, such as Headland Partners (D. Sellers and B. Godsey), have also generated outsized returns, exiting their acquisition for an 11x investor return.

So, why do so many searchers go solo?

The 81% that go solo are making a rational bet on variance over the mean. Leveraging a second view is a safer path to a high return. Solo searchers are rejecting that safer average and accepting a lower probability of success, in exchange for a 100% claim on the entire prize.

Explaining the Gap in Success Rates: International vs North America.

There is a striking difference in international acquisition success rates (79% vs. 63% in the US/Canada). While the studies do not provide a single definitive cause, a primary hypothesis is market maturity. International markets are, on average, younger, with the model expanding to many countries only after 2003. This may suggest a larger, less-picked-over supply of available businesses along with lesser competition for the same deals.

The 2019 acquisition of OKM detectors in Germany is a perfect illustration of this. The searcher, Stephan Grund, was a business-school graduate and former strategy consultant, perfectly matching the ideal searcher profile. He launched a search in Germany and successfully acquired OKM, a leading German SME manufacturing metal detectors.

Grund's success (part of the 79% rate ) occurred in a market that, while economically mature, is an emerging market from an ETA perspective. The "less-picked-over" hypothesis is substantiated by macro-environmental data: between 2018 and 2022, Germany had over half a million SMEs seeking successors, and Finland had over 78,000 owners set to retire.

A second factor may be a behavioral difference. The 2022 IESE study noted that some international searchers who fail to find a suitable acquisition will occasionally pursue a startup in that sector with the agreement and support of their search fund investors. This path, while not a traditional acquisition, avoids a failed search. This suggests the 63% US/Canada rate may actually reflect a more disciplined market, where investors are more willing to say "no" and accept a failed search as a successful, disciplined outcome rather than funding a deal outside their defined parameters.

The Target: Sourcing, Selection, and Valuation

What a “Good Horse” Looks Like.

The definition of a "good horse" remains remarkably consistent. The criteria established in the seminal 2014 IESE report, which include a history of profitability, a high component of recurring or repeat revenue, low CapEx requirements, and operating in a growing, fragmented industry, are still the ideal. These criteria are aimed at reducing risk for a first-time CEO.

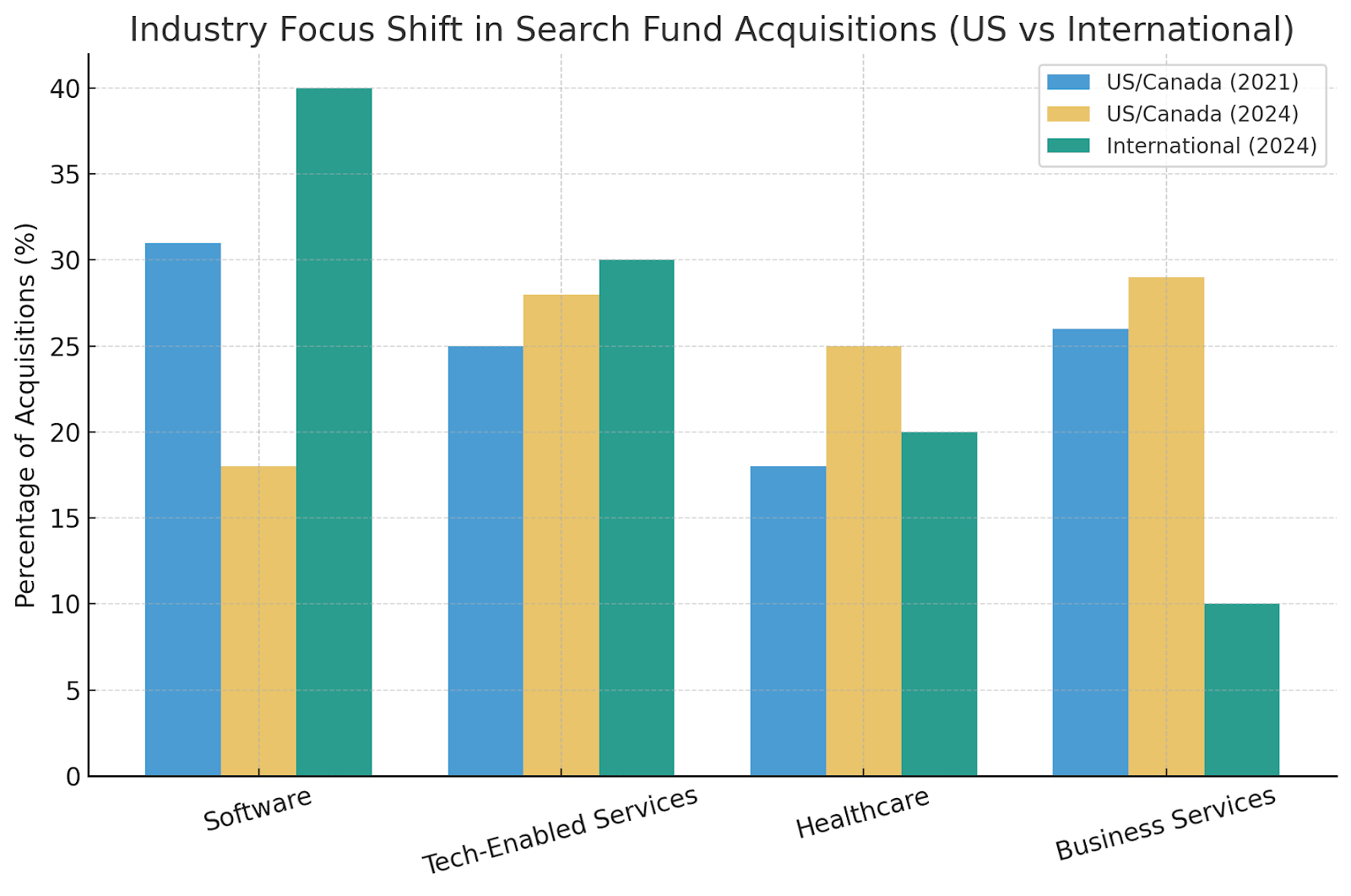

The rise of software and tech-enabled services has not changed this definition; rather, these industries often fit the criteria perfectly, which explains their popularity. For instance, a high percentage of international searchers target the technology sector. However, recent data from the 2024 Stanford study indicates a slight moderation in the US and Canada, with fewer recent acquisitions in pure software and a continued strong focus on tech-enabled services, healthcare services, and other business services.

Explaining the Multiple Gap.

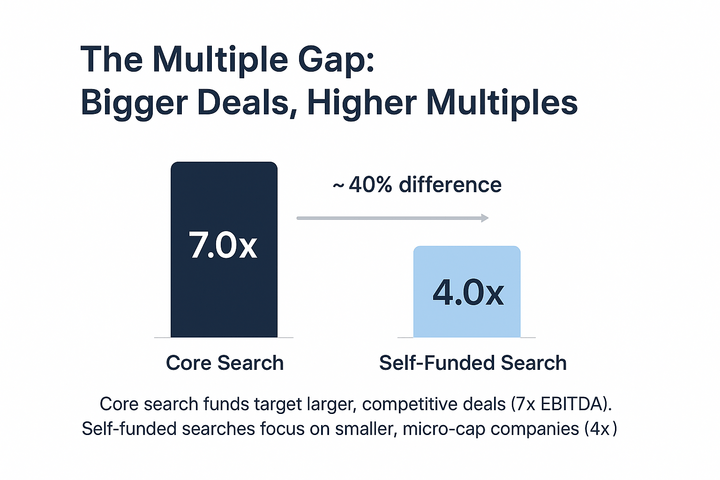

This multiple gap is less an indicator of business quality and more a function of two different models. The core model, which targets larger deals with a median purchase price of $14.4 million at a 7.0x EBITDA multiple, operates in a more efficient and competitive deal environment. These larger deals are more likely to be run as competitive auctions, attracting private equity firms and strategic buyers who can drive the price higher.

The self funded model, by contrast, targets more of the micro cap segment. Typically companies with $500,000 to $2 million in EBITDA. This market is generally too small for traditional PE, creating a less competitive, inefficient market where 3.0x to 5.0x multiples are the norm.

Chenmark Capital, a holding company founded by Trish and James Higgins, is a premier real world example. Chenmark acquires a portfolio of small, non-glamorous, cash flowing travel businesses, such as the Buccaneer Pirate and Southern Star Dolphin Cruise. This type of seasonal business is too small for institutional PE and fits perfectly within the self-funded target range. These are precisely the types of businesses (e.g., home services and commercial maintenance services) that trade at the 3x-5x multiples.

How are Searchers Sourcing their Deals?

Proprietary sourcing is essential for any successful search, often acting as the make or break factor separating a successful search from the rest.

The 2024 IESE study identifies "Proprietary Exploration" as the most common deal sourcing approach, used by 64% of searchers. Its importance lies in finding businesses that are not actively for sale, which means a less competitive bidding process and lower price.

Some advanced proprietary methods include conducting deep industry research, attending trade shows to gain credibility, and engaging "River Guides." These guides are typically retired industry CEOs or trade association presidents who are compensated to provide warm introductions to potential sellers, which is a highly effective way to establish credibility.

The Deal: Due Diligence, Negotiation, and Failure

Why Do Deals Fail Post-LOI?

The period between signing a Letter of Intent (LOI) and closing the deal is arguably the most important. The data shows exactly why this phase fails and how to manage the process.

The 2024 IESE study identifies the top reasons LOIs fail as problems discovered during due diligence (63%) and issues related to valuations (48%). These two findings are directly linked. They describe the most common and predictable crisis point in a deal.

A searcher, for example, signs an LOI based on a seller's represented $1.5 million EBITDA. The searcher then commissions a third party QoE report, which is the primary tool for discovery during due diligence. The tactical playbook for when that report shows an adjusted EBITDA of only $1.1 million is not to view it as a failure, but as the process working correctly.

The conversation with the seller must be direct, data driven, and respectful. The searcher should frame the QoE as an objective, third party validation that both sides need to get the deal done. The conversation is then straightforward: the initial offer was based on $1.5 million in earnings, and the new, verified number of $1.1 million requires a proportional adjustment to the valuation. It needs to be a renegotiation, not an accusation.

How to Handle Seller Considerations.

This leads to the third major reason for failure: seller retraction (38%). This statistic proves that a searcher is acquiring a business from a person, not just a set of financials. For many owners, this is an emotional process of selling not just the business, but also their life's work. Work that they have dedicated decades to. Hence searchers must understand how to treat all potential acquisitions with the utmost care and respect. If the seller does not think you can genuinely take ‘their baby’ forward then the deal is never going to happen, no matter what you offer them. To efficiently conduct due diligence on the seller, the searcher must, from the first meeting, work to understand the seller's true motivations.

Are they truly ready for retirement? Are they solving for non financial legacy outcomes? A seller who is not genuinely committed to a sale, or who is just looking to see what kind of offers they get, is a significant waste of time and energy. Building trust and maintaining open, constructive communication is the only way to ensure a seller sticks through the long and difficult acquisition process.

When to Walk Away?

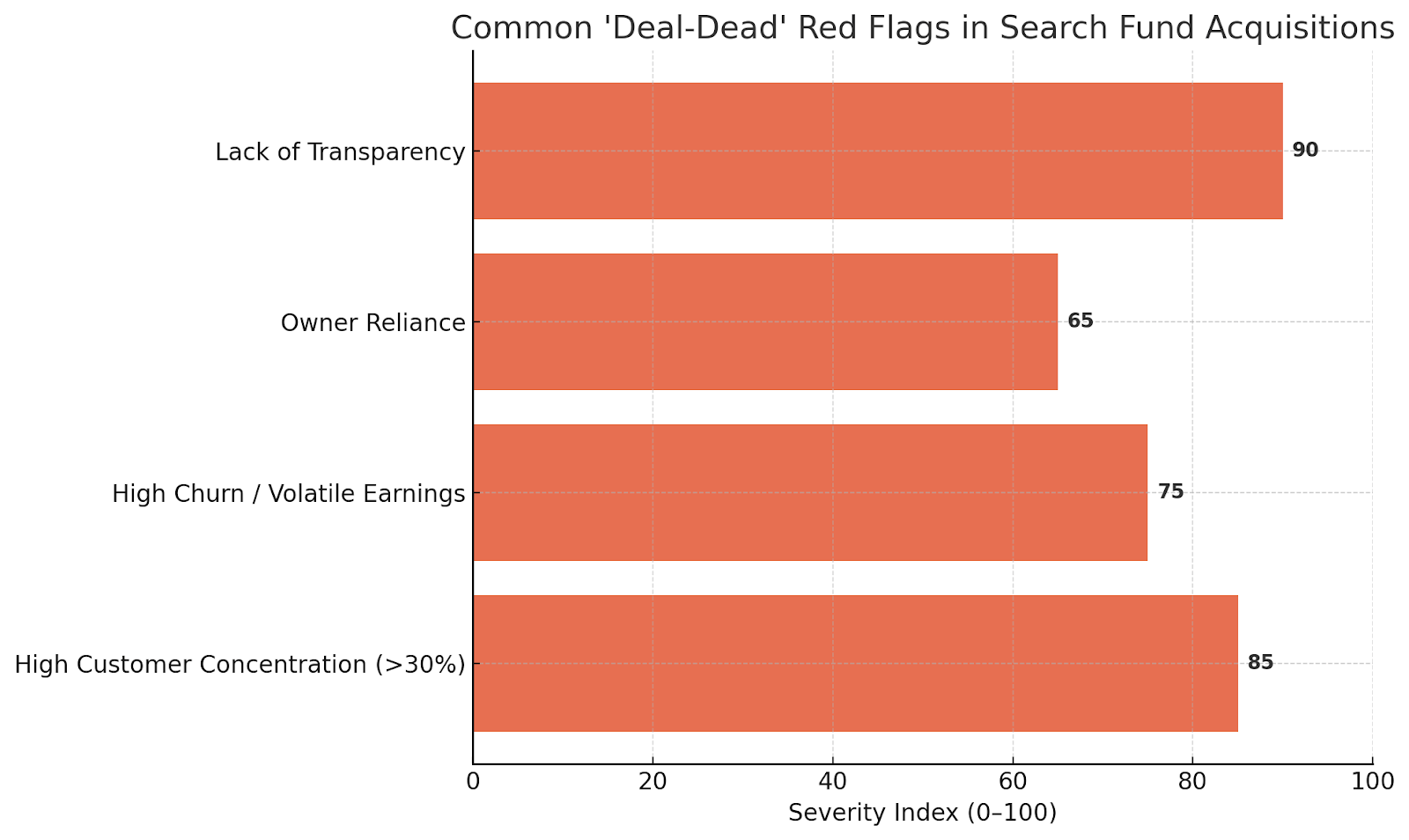

Finally, a searcher must know when to walk away. A "deal-dead" red flag is any discovery that breaks the fundamental search fund thesis. Searchers should avoid turnaround situations. They are looking for stable, profitable companies, not broken ones.

Other non-negotiable red flags include high customer concentration (for example, one customer accounting for over 30% of sales), high customer churn, or volatile earnings with no visibility. Perhaps the biggest red flag of all is a seller who is not transparent or who actively obstructs the diligence process. This indicates a critical lack of trust and suggests the information asymmetry is likely hiding a fatal, unfixable flaw.

The Exit and Final Reflections

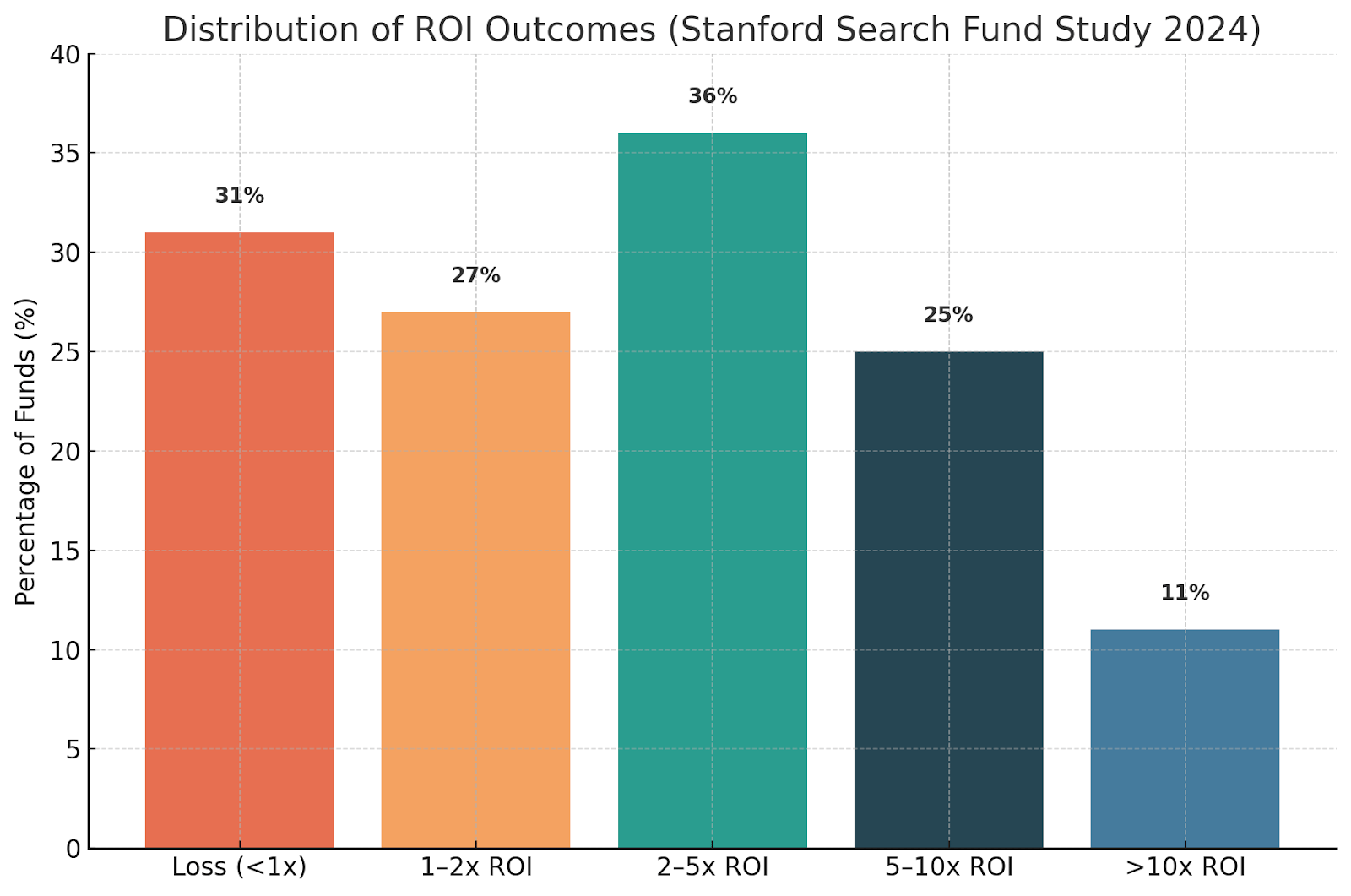

The 2024 Stanford data indicates a "barbell" or "tale of two cities" distribution of returns. This is the central risk and reward of the search fund model. The 11% of acquisitions that achieve a grand-slam, greater than 10x ROI are often separated from the 31% that result in a loss by the quality of the asset.

Losses, conversely, are often linked to acquiring turnaround situations, businesses with high customer concentration, or those in volatile, unpredictable industries.

The choice between the core and self-funded models is a direct and personal trade-off between risk and reward. The data confirms the median exited payout for a core searcher is $2.25 million. This path offers significantly lower personal risk; the searcher receives a salary during the search and investors bear the financial risk of a failed endeavor.

The self-funded path is a high-risk, high-reward bet on oneself. The searcher forgoes a salary putting themselves at risk of personal bankruptcy. The explicit return for taking on this risk is retaining a substantial majority (usually 60%+) of the equity.

The best advice is to make the often personal choice based on an honest assessment of one's personal financial cushion and psychological tolerance for high-stakes, personal liability.

Bibliography:

Benjamin, Elad, et al. Search Fund Primer: A Practical Guide for Entrepreneurs Embarking on a Search Fund. Stanford Graduate School of Business, May 2021.

Harvard Business Review. How Search Funds Are Redefining Entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 2019.

Hurst, A., & Pickenpack, L. Foundational Guide to Self-Funded Search Funds. Searchfunder.com, 2021.

Kowalewski, Ann-Sophie, et al. International Search Fund Study 2024: Selected Observations. IESE Business School, Sept. 2024.

Kolarova, Lenka, et al. IESE Search Fund Study 2022: Selected Observations. IESE Business School, Oct. 2022.

Leung, Yannie, and Christina Stiles. Entrepreneurship through Acquisition – A Scoping Review. Harvard Business School, 2022.

Ruback, Richard S., and Royce Yudkoff. Search Funds—What Has Made Them Work? IESE Business School, 2016.

Stanford Graduate School of Business. 2024 Search Fund Study: Selected Observations. Center for Entrepreneurial Studies, 2024.

Reply